Bala Tikkisetty, sustainable agriculture advisor (technical) at Waikato Regional Council.

With winter not too far away, this is the time for planning for tree planting.

Planting a shelterbelt is an option for some livestock farmers to reduce the adverse effects of inclement weather.

Whether it is hot or cold, climatic conditions may lower productivity by reduced grazing periods and therefore reduced feed intake. Windy conditions enhance the loss of moisture from both soil and pastures which results in reduction in overall dry matter growth.

The traditional view is that shelterbelts help to reduce evaporation of soil moisture and transpiration from the grass. Live shelter is particularly helpful in drought or prolonged dry spells.

In addition to environmental benefits such as soil erosion control, shelter can have complementary effects by achieving multiple goals for both the landowner and the environment.

Shelter trees can be a haven for birds, give shelter for homes, buildings and stock yards, be aesthetically pleasing and increase the tree species in an area. This is one of the greatest ways of increasing biodiversity. Shelter can also screen noise and reduce odours associated with livestock operations.

The use of native plants, particularly those naturally occurring in the area, help to preserve the local character and provide forage for bees.

Strategic planting is likely to be more worthwhile than blanket planting and because of the long term commitment, a careful decision should be made.

Shelter is most effective when sited at right angles to the prevailing wind. If east-west shelterbelts are required they should include deciduous species to lessen the winter shading of pastures.

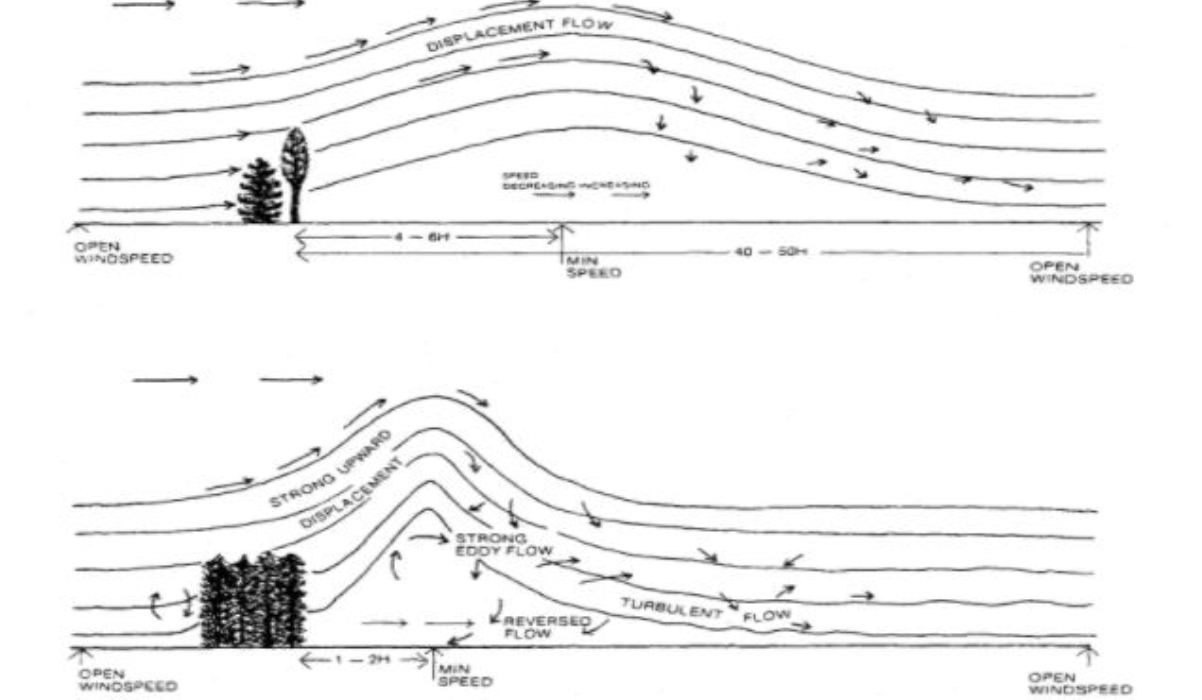

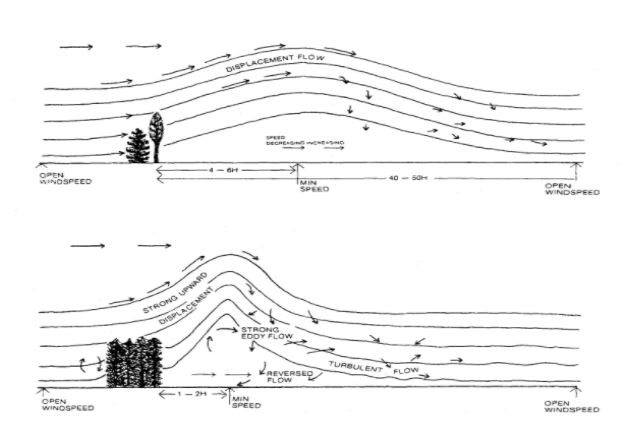

Practical experience has shown clearly that belts of medium porosity (about 50 per cent) produce a much more even wind flow over a much wider area. Good porosity can be achieved by correct species choice and subsequent management. When porosity is low, the wind profile is changed; turbulence occurs at a factor of about five times the shelter height.

The longer the windbreak the better the protection. Short plantings have a disproportionate edge effect, where wind slips around the ends reducing the area of protection. Gaps in a shelterbelt cause the wind to funnel through at excessive speed. This can happen where there are missing trees or when there is a draughty space at ground level.

Height of the shelter directly influences the area of wind reduction on the leeward and windward side. Tall shelter gives the most economic protection as the area protected is directly related to the height of the windbreak.

These days, people regularly ask us for some information for carbon farming. Any tree species (other than those grown mainly for fruit or nuts) can be used in carbon farming, so long as they reach at least 5 metres in height and the forest after 12 years has:

- at least 30 per cent tree canopy cover

- an average width of at least 30 metres

- an area of 1 hectare or more.

Fast growing trees like radiata pine and Douglas fir planted in closed canopy forests are the most profitable for carbon forestry because they store (sequester) the most carbon in the shortest time.

Species that have other attributes (biodiversity, speciality timbers, amenity, etc) may be included in a carbon forest. Space-planted willows or poplars can be part of a carbon forest, but their carbon yield will be low.

Bala Tikkisetty is a sustainable agriculture advisor (technical) at Waikato Regional Council. Contact him on bala.tikkisetty@waikatoregion.govt.nz or 0800 800 401.