Continued from Part 1 in 9th Feb post. – By John Lawson

Vehicle crashes and ongoing road works on the Raglan Road are nothing new. Earlier in 1922 the Reform MP’s car, “came into collision with a car driven by Mr Garnmonsway, on one of the bends” on the deviation. Shock and bruises were the worst injuries and, “Mr Bollard’s car was brought into Hamilton with the radiator and lamps smashed.”

Later in the year some dangerous bends on the deviation were widened and, “Extra hands have been employed on the deviation owing to recent slips.” As part of those works, 10-mile and 13-mile quarries were developed, near Heddon Rd and the top of the divi. Gravel was also taken from the Mangakino and Waitetuna streams for the main road. A quarry was also opened near the Waingaro Landing Road junction. The Kauroa Butter Factory to Te Mata road was among others improved in 1922. For that work, “The Council’s crushing plant from Te Uku has been shifted to Gibbison’s Quarry, and about seven chains of tramline laid from the plant to the quarry” and Jerome’s deviation bridge straightened the road near Te Mata. Other roads improved were Mangati to Te Akau Wharf and to Dunmore, Heddon, Kohanga, Makomako, Cogswell, Okete, O’Shea Road, Pakihi to Okete, Pond’s, Ponganui, Te Uku Landing, Vandy, Wainui, Waitetuna to Waipa, Whaanga, White’s, Opotoru Bridge approach and Opuatia, Pakoka and Mangaokahu bridges.

In January 1922 the boiler at the Dairy Factory failed. Until a new one was installed in March, the cream was for the first time trucked to New Zealand Co-op at Frankton. J. P. Porter won the cream carting contract for Raglan Dairy “at a considerably lower rate than previous seasons”, with a 2½ ton Dennis truck on solid rubber tyres. Gravel roads and trucks cut the road freight between Raglan and Te Mata from £4 5s to £1 per ton. However, Te Mata’s roads still weren’t metalled, so the trucks spent the winter parked where the metal ended on the Kauroa Rd. Cream and other goods were still carted that far by horse power.

Butter production at the Wallis St factory rose from 92 tons in 1921 to 149 tons in 1922 (from 90 farms), 220 tons in 1923 and 235 tons in 1924, helped by a 100 ft. bore, drilled through through 20ft of papa rock in 1922 and producing 500 to 600 gallons per hour. Before the 1964 water scheme it was used for town water.

When the dairy company asked Raglan County Council to reduce charges for butter shipped from the wharf, they got a sharp rebuke from RCC chairman, Campbell Johnstone, who said, “The dairy company . . . used motor lorries on our roads at considerable expense to the ratepayers. . . It’s ridiculous to expect us to sit here and listen to such absurd twaddle, and I for one am not going to stand it.” Campbell Johnstone owned Whatawhata coal mine. A few months after rejection of the wharf request, the dairy AGM passed a motion, “That this meeting of shareholders and ratepayers views with alarm the damage being done to the road between Whatawhata and Hamilton by certain mineowners in using the road for heavy loads, which had resulted in considerable damage being paid for at present by the Raglan ratepayers, and that strong representations be made to the County Council and the Minister of Roads and Bridges, that the mineowners who do the damage and not the ratepayers be taxed for its upkeep.”

Whatawhata coal mine was developed in 1922. It had a 14 feet thick seam, a couple of hundred yards from the main Whatawhata-Raglan road, and was linked to the road by horse drawn wagons on a wooden tramway. The mine closed when Hamilton gasworks was replaced by a gas pipeline on 25 March 1970.

Whether the Whatawhata bridge should be replaced in concrete or wood was debated several times during the year. Raglan County chose the cheaper wooden option. RCC also changed its engineer, paying the new one £450 a year.

Plans were also being made for the first footbridge; 320 ft long, 6ft wide, though it didn’t open until 1926. It was estimated at £1,600 and was to be near the corner of the bathing enclosure. The final cost was £2,500. The Raglan Town Board repaired the bathing shed and improved the bathing enclosure, because, “The bathing place is one of the chief assets of the town.”

Although new changes were coming and dairying was increasing, much of the old remained. Crops still included oats, potatoes, turnips and kumeras and government experts came to give demonstrations of rabbit-poisoning. A team of horses drawing a dray took fright at the council’s oil tractor, and backed over a bank into a stream at Te Uku, though no damage was done. The steamers continued their weekly link with Onehunga. Rimu (412 tons), the usual steamer serving Raglan and Kawhia, was in for repair at the start of the year, so Arapawa (291 tons) was covering the run, until Aupouri (463 tons) took over in March. So it was on Aupouri that, “A goodly number journeyed to Gannet Island on the annual fishing excursion, but owing to the heavy swell no hapuka fishing could be had. The vessel had to shift to the schnapper beds, where good sport was had, including a 7ft shark.” Raglan to Kawhia took around 2¾ hours, from wharf to wharf when Rimu was running well. When it wasn’t, or the Arapawa was on the run, it could take over 4 hours, or even up to 8 hours in bad weather. Rough seas at the Manukau bar also delayed ships several times during the year. Aupouri again took over in September, when Rimu went to work the New Plymouth route. Aupouri was the last ship to join a 3-week strike in November, because the weather was too stormy to leave Raglan. Northern Steamship cut its charges to meet rail and road competition and then cut wages, resulting in the strike and the use of “free labour” to run the ships. During the strike a report said, “flour has been exceedingly scarce” in Raglan, showing that much food still travelled via the steamers. Work also continued to improve the wharf at Ponganui, on the Te Akau Wharf Rd, as launches and barges still moved goods around the harbour.

The road from Pakoka to Kawhia was still very poor, so for a couple of months an attempt was made to combine the old and the new, with a launch across Aotea Harbour, connecting with a Cadillac or Buick service car via Te Mata to Frankton. It was a scenic route, but dependent on tides, so gained few passengers.

One report said, “There are many kiwis and wekas seem to be everywhere.” Milling of rimu on Karioi continued, but Raglan Chamber of Commerce approached Te Toto gorge owner, J. F. Jackson, and he agreed, “to keep the same intact for all time.” Also in 1922 Hamilton Chamber of Commerce urged the Government to set aside part of the Moerangi Block as a national park. In January 1922 it was reported that “the tattooed rocks at Raglan have been, seriously damaged by the use of explosive, one being split in two parts.”

On the slopes of Karioi, work began on Bryant House, now the Bible Camp. The site was cleared, levelled, fenced, sown with grass and heart of rimu timber was delivered for a building to accommodate 48 children, “close to the famous camping ground at Whale Bay.” The council also agreed to improve Wainui Road (known as Bryant Home Rd for about 50 years from the 1930s), though it was a few years before they got a government grant to gravel it.

Aramiro store was started by Mr Rupa about 1922 and continued until the rural population decline of the late 1950s.

Connie Bernard, later well known as a baker and for work with the carnival and protecting Bow Street’s pohutukawas, was appointed to teach at Raglan School. She took the train to Frankton, then Robertson’s service car to Raglan. She stayed at Mrs Foss’s boarding house, opposite where the fire station now is, along with staff from the Post Office, Dairy Factory and Chronicle, a tailor, Jimmy Laughton, and the congregational Minister. Connie married in 1926.

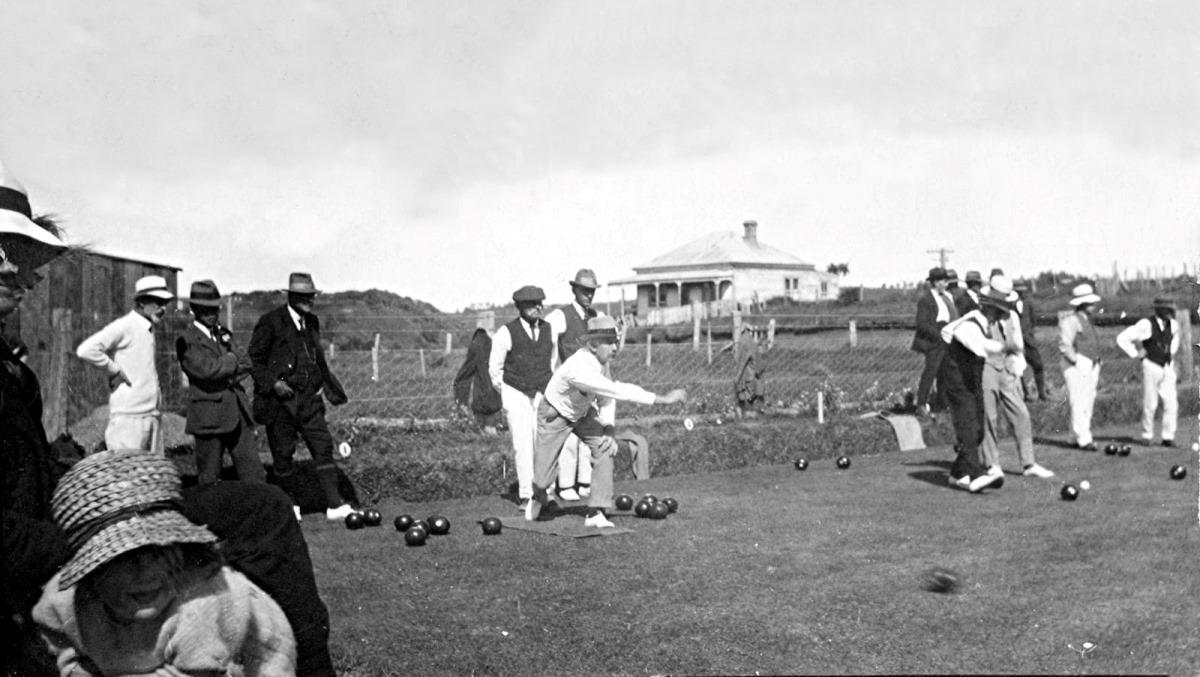

By 15 May 1922, the Bowling Club had £89.19s.0d. in its Post Office Savings Bank and in July Mr Gleeson appointed as Greenkeeper for £5 a year. His work resulted in the first games being played to the music of the Raglan Band on the afternoon Saturday 18 November (see photo – which house is in the background?), when the new green was officially opened. Hockey and tennis were other popular Raglan games in 1922. Connie later wrote, “The Tennis Club was the chief centre of social life. All young folk belonged and the social side was as important as the game.”

Raglan Boy Scout troop changed to being sea scouts and got a lifeboat from the old Amokura training ship. A Town Hall concert for the boat fund raised £18 3s. It was one of many concerts, dances, etc. There was no TV, radio was only just starting and cinema didn’t reach Raglan till about 1923. As well as dancing and concerts, there were plain and fancy dress balls, lift dancing, farewell socials, guessing competitions, recitations, community singing, quoits, cards, ping-pong, old-fashioned games and a leap year supper dance, often till the small hours of the morning. Others organising them included Te Uku Girls’ Hockey Club, St. Peter’s Church, Te Mata Anglican Ladies’ Guild, Waitetuna school, Karioi Football Club, W.O.T. Football Club, Te Mata and Waitetuna Tennis Clubs, Waitetuna Basket Ball Club and Raglan Kewpie Club (Kewpie were cartoon characters, produced as dolls in the 1920s). The main venues were Te Mata Hall, which had a supper room added in about 1922, Te Uku Memorial Hall and the Town Hall, though Waitetuna had a monthly social in the schoolroom and music was provided by Raglan Town Band and/or Orchestra and several other locals.

Changes were gathering pace.